What Will Break First In The Increasingly Difficult Leadership Juggling Act?

Focus matters most in leadership. And the priorities competing for leaders' focus today is creating significant burnout

In serving as CEO of a company for 14 years—and having gotten to know hundreds of other company leaders personally—I have noticed an evolution in the expectations placed on top executives over the past decade.

CEO is an immensely complex role. But, counterintuitively, a CEO is most effective when they tune out as much of the noise as possible and focus on the few things that matter most for the business.

Historically, most CEOs have primarily focused on stewarding two main areas of their companies:

Core Product/Market: Ensuring the product the company is selling is effective and strongly fits the market of both today and tomorrow. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll call this Product going forward.

People, Culture and Operations: Ensure that the right people are in the right roles and maintain a culture and operating processes that put those people in the best possible position to succeed. We’ll call this People/Ops going forward.

Generally speaking, the CEO needs to direct equal focus toward Product and People/Ops in order to keep the company healthy and competitive. Excelling in just one of these areas won’t lead to sustainable success.

For example, Nokia was a well-respected company with efficient operations and a seemingly healthy culture. But they failed to adapt to the meteoric rise of smartphones, and the company rapidly lost its dominant market position once customers abandoned Nokia’s core product for the iPhone and Android.

On the other hand, Uber offered a product that was extremely popular with investors and customers alike. However, a toxic culture nearly derailed the company just as it reached its peak.

This is why, even though a CEO must occasionally focus more intently on either Product or People/Ops, they must always keep an eye on both of these areas. Below is a good illustration: The CEO’s focus is perfectly balanced between the edges of the Product and People/Ops boxes:

The CEO Focus circle above cannot expand to fully cover both boxes. That circle’s size is constrained by two basic facts of life as a CEO:

There are not enough hours in the day for a CEO to do everything asked of them.

A company is most effective when its CEO obsessively focuses on the few priorities that matter most to the business’ health. Even within the Product and People/Ops fields, everything that is not truly essential must be delegated to the broader team or deprioritized entirely.

This is why the CEO Focus circle in the chart can only span a portion of each box in the long run. Their role is not to know everything; it’s to set the direction for their executives to execute, monitor key metrics in each area, and ensure the team delivers what is required—or adjust course as needed.

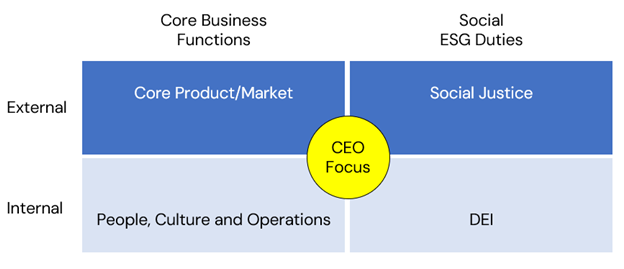

In recent years, the CEO’s area of responsibility has drastically changed due to the emergence of Environmental, Social and Governance duties, also known as ESG. It’s important to understand what ESG responsibilities involve:

Environmental: Typically, this involves issues like waste reduction, energy efficiency or investment in renewable energy. This is often easily delegated and can be monitored with clear metrics and regular reporting.

Governance: This includes improving board diversity, enhancing corporate transparency, or implementing more robust risk management processes. As with environmental issues, these are typically delegated within the People/Ops function and only require CEO involvement if there’s a major issue.

Social: This component of ESG is where things get far more complicated. These responsibilities are broader and may include formal diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) efforts as well as taking stances on social justice issues. Because these duties require navigating complex social dynamics—with widely varying expectations from various stakeholders—and because mistakes can be quite damaging, they are harder to delegate.

Taken in the aggregate, these social ESG duties have added a lot to the CEO’s plate, while nothing has been removed.

Referring back to the original chart of the CEO’s focus, let’s place the social aspects of ESG on the same External/Internal divide:

As you can see, the CEO today has two additional areas that are demanding their attention on top of their existing responsibilities. Given an even distribution of focus across the four areas, that means time spent in the crucial Product and People/Ops boxes is often meaningfully diluted.

To be clear, I am not arguing against the benefits of DEI. It’s an important issue for a growing number of employees today, and data shows organizations that are diverse and inclusive outperform competitors in the long run. But it’s crucial to understand that when DEI and social justice become corporate imperatives on the same footing as Product and People/Ops, there may be unintended consequences.

DEI has rapidly emerged internally as a top priority for many C-Suite executives. Many DEI roles and initiatives have been elevated beyond the traditional structure of the HR or culture team, requiring new investment of time and resources, such as the creation of Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) that often have executive sponsors. It’s clear that DEI is demanding more resources and attention from the executive level than ever before.

On the external side, companies now more frequently take more public stances on non-company issues. Many CEOs and leaders today are expected to weigh in on social issues; however, that requires navigating a diverse range of social causes, societal problems, and possible solutions that employees want leaders to evaluate and opine on. At the same time, acting on these social justice topics rarely makes everyone happy—while taking a certain stance may resonate with some employees, it may alienate others. People very often disagree on solutions, even if they agree on the problem.

Essentially, CEOs have seen their core responsibilities double in the past several years, with the same number of working hours. And a CEO cannot simply shift all their focus to DEI and social justice to make those stakeholders happy, as doing so creates consequences for the Product and People/Ops areas.

While no one expects the average person or employee to shed a tear for the plight of a CEO, this juggling act has a real cost—not just for the leader, but also for the organization and everyone it touches.

Leadership Burnout

First, there’s the burnout issue. Employee burnout is a widely discussed topic, but less attention has been paid to how quickly burnout rises to the top in organizations. It’s probably not a coincidence that, as their responsibilities double, leaders are starting to feel the strain of so many priorities competing for their time and focus. Harvard Business Review found that 50 percent of leaders feel burned out. CEO turnover is also reaching record levels. Even Boards of Directors have reported feeling burnout.

This is not a coincidence. While the challenging macroeconomic environment of the past two years—and the lingering exhaustion of leading during the pandemic—has played a big role, so too has the fact that new ESG responsibilities have made leaders’ jobs more difficult and expansive. What was once a two-item scorecard is now a four-item one, and CEOs have less energy to tackle these issues after a few hard years.

Having often discussed this new reality with company leaders and executives, I sense many are feeling the pressure of balancing their focus on these current competing priorities. It’s not that they don’t find all these areas important; the reality is just that it’s nearly impossible to simultaneously give all of them the attention they demand and deserve.

If a leader gave each of their employees two new major areas of responsibility and told them they’d be expected to add those to their workload for the same pay, they’d quickly have an angry mob of employees on their hands. This is the reality I suspect the vast majority of leaders currently face—they just don’t feel safe admitting it out loud, other than when in groups of their peers. They are stretched thin, juggling plates from these four quadrants, wondering which one is going to break first and how that breakage will affect the greater business. Yes, we should expect more from our leaders, but they are also human like everyone else, and everyone’s capacity has limits.

Company Focus

The second core problem is the dilution of company focus.

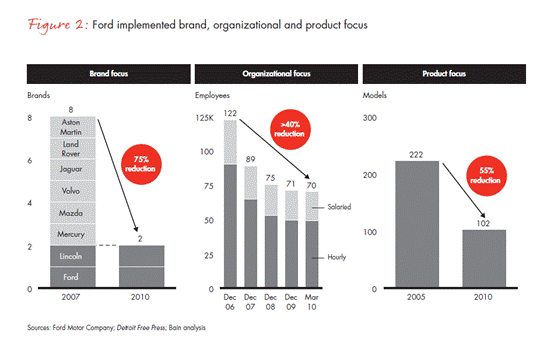

As stated earlier, it is important to keep the CEO’s focus homed in on what is most important. Alan Mulally's tenure as CEO of Ford is a textbook example of the power of focus.

When Mulally took the CEO job in 2006, the company was facing record losses, a declining market share, and a dysfunctional corporate culture. In response, Mulally instituted the "One Ford" plan, a strategy that created a unified, global Ford brand and focused the entire organization on making that brand successful. As a result of this, Ford was the only American automaker to avoid bankruptcy during the financial crisis. In 2010, as most of the auto industry foundered, Ford reported a net income of $6.6 billion, its highest in over a decade.

Focus is the hallmark of great businesses and great leaders, and the additional social requirements of leadership—no matter how well-intentioned—are a threat to that focus. If we accept the assumption that leaders can’t expand their area of focus, then they are left with two options: dilute focus overall, or make tough decisions and shift the lens of focus based on the current business needs, prioritizing certain areas over others.

Here’s the focus chart again:

Again, you will notice that because the diameter of the CEO Focus circle stays the same, the CEO can either give a comparatively small amount of attention to all four areas or it can ignore one or more areas entirely for some period of time. And while a CEO can delegate initiatives in these focus areas to their teams, CEO and executive team involvement is typically required to drive major changes in an organization.

Here’s the brutal truth: not everything can be a priority. Some companies, and their employees and boards, need to recognize that time spent on social issues will inevitably cause erosion in Product and People/Ops. We are seeing that play out in today’s challenging business environment, where very few companies are thriving.

Disney offers a prominent example of this dynamic. The entertainment giant is essentially fighting a two-front war in its business. First, its stock price has dropped over 25 percent since February 2023, driven by a slowdown of growth and profitability concerns in its streaming business, coupled with some embarrassing movie flops. As it battles that significant Product issue, Disney has simultaneously fought a very public culture war with Florida governor Ron DeSantis since Spring 2022.

It’s true that Disney’s political battle is not the primary reason for its unsteady business performance. However, whether you agree with Disney’s actions or not, it’s undeniable that the conflict has taken some portion of the Disney leadership’s focus and energy at a time where they have major challenges in their core business.

An even more recent example comes from Boeing, which continues to be plagued with problems involving its new 737 MAX airplane. The 737 MAX emerged from a culture that prioritized efficiency over safety, resulting in two unprecedented crashes of this new model that killed 346 people combined. After these tragedies, Boeing grounded the aircraft and vowed to fix safety issues with the airplane before returning it to circulation.

Shortly after Boeing grounded the 737 MAX in late 2019, the company spent much of 2020 making an extremely public commitment to ESG initiatives at the company. The firm invested over $10 million in DEI initiatives, crafted carefully worded ESG pages on their websites and have attempted to strengthen their reputation with splashy reports designed to rebuild some of the credibility the manufacturer lost due to the 737 MAX’s fatal issues.

Despite making headway on the ESG front, the 737 MAX has continued to be plagued by delays, problems and safety issues. These challenges culminated in a recent accident where the door blew off a 737 MAX 9 during a flight in January—this resulted in the 737 MAX planes being grounded for weeks and a plunging company stock.

To clarify, the recent accident involving Boeing was not directly caused by the company's intensified efforts to build diversity. However, it is evident that Boeing's primary business challenge in recent years has been maintaining quality and safety standards, areas where leadership seems to have lacked adequate focus. This oversight has significantly damaged the brand and has led to substantial financial losses. The company’s ESG investment required time, effort and focus from leadership, and it diverted attention from a desperate need to fix their most important new product.

For a more general example, consider the threat many businesses are facing today: artificial intelligence. If the rise of AI has suddenly created a potentially existential threat to your core product, or if AI offers the opportunity to revolutionize your business’ operations, how much focus can you afford to dedicate to issues outside your company’s walls, such as the latest political battle? What prioritization order is in the best interest of your employees and culture? While social justice and DEI are extremely important to employees, those same employees probably won’t be well served if AI disruption causes a Nokia-type loss in market share that leads to mass layoffs or bankruptcy.

Employees don’t always see the big picture in this way, but these are the tough choices leaders face daily, with finite time and resources. The reality is that sometimes you just have to focus on the alligator closest to the boat.

The future of DEI and social justice at work

There’s not a clear answer to this problem, but I think it needs to be discussed more openly among leaders, in board meetings, and with employees. In the long term, my best guess is that DEI will find a more permanent home within the People/Ops area, where it will be a more seamlessly integrated part of the organization, rather than its own priority at every executive offsite and board meeting.

We are also still in the R&D phase of DEI, which means that many companies are trying several new things without the data or experience to know which initiatives are truly improving equity and inclusion, and which are less effective or even counterproductive. One common misstep that has already been identified is perfunctory diversity trainings, which have been widely criticized as ineffective, despite companies spending billions of dollars a year on them. Many of these trainings are also delivered by individuals without the requisite credentials or experience.

This type of trial-and-error is common with any high-growth initiative. Eventually, companies will figure out what moves the needle and what doesn’t, gaining better results with more focus.

I suspect there is not a similarly clean endpoint for company involvement on social issues, especially for businesses that aren’t consumer-facing brands. While the loudest voices in a company push for more social statements and involvement from their leaders, not all employees want that level of external engagement, especially on hot button political and social justice issues.

For example, Gallup found that only 48 percent of employees want their companies to take a stand on political and social issues. There’s hardly a consensus on the best way to handle social and political topics—either way, leaders are going to leave large numbers of people feeling alienated.

Leaders of large multinational organizations will have to consider the potential impact of their decisions on their brand and global operations. In a world where companies operate across borders and cultures, a stance that resonates positively in one region may provoke an uproar in another. There’s also the real risk of creating double standards, which can rub employees, partners and customers the wrong way.

For example, the English Premier League’s Arsenal Football Club, owned by American billionaire Stan Kroenke, found itself embroiled in an international incident in 2019 when Muslim player Mesut Özil spoke out against the oppression of Uighurs Muslims in China, which many human rights groups consider a modern-day cultural genocide. Özil's remarks prompted China, a major market for Premier League soccer, to temporarily refuse to broadcast Arsenal games. In response Arsenal quickly distanced itself from Özil, saying in a statement that Özil's comments were a “personal opinion” and that “Arsenal has always adhered to the principle of not involving itself in politics.”

However, Arsenal changed that principle the following summer after George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police. The club, like many in Premier League, replaced players’ names on their jerseys with the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” and released a statement specifically supporting players who spoke out in support of the movement. However, the club did not attempt to make any amends with Özil. In fact, he was essentially exiled from the club in the 2020 season, a year after the club declared that they don’t get involved in politics but did just exactly that just months later.

This is not to say that Arsenal should not have shown solidarity to the cause of racial justice. But the club’s decision on Özil suggests that freezing out the Muslim star in one moment and championing racial equality in another were actually business decisions, not moral ones. I suspect many Muslim fans took note of the double standard.

One future that seems feasible is an environment where a B2B SaaS company with no consumer-facing products and a handful of employees may choose to avoid weighing in on every social justice issue, but a global consumer brand with a diverse customer base may see doing so as essential to their brand and values. Both approaches ought to be completely acceptable. The key is for companies to be thoughtful, intentional, and authentic in their approaches, rather than reactionary or performative. They should also make that approach clear to their employees.

Several companies have taken this path, sharing with employees that they simply won’t be focusing on social issues. For example, 37signals, the company behind the popular software Basecamp, offers the following paragraph on its jobs page:

“We respect everyone’s right to participate in political expression and activism, but we avoid having political debates on our internal communication systems. 37signals as a company also does not weigh in on politics publicly, outside of topics directly related to our business. You should be at peace with both of these stances.”

Some current and potential employees are turned off by this, and others are relieved. This is a good free market at work: companies state their value propositions, and employees decide which one they want to work for, just as they’d choose between a remote company and an in-office one.

The role of a leader, and particularly of a CEO, has undeniably become larger and more complex in a short period of time. Balancing the traditional responsibilities of Product and People/Ops with the emerging priorities of DEI and social justice is a high wire juggling act. Doing so effectively requires a delicate balance of focus, prioritization, and an ironclad understanding of the company’s business needs and its place in society.

The burden of this juggling act is a topic that should be discussed at all levels of an organization, from the boardroom to the break room. Leaders need to be transparent about the challenges they face, the choices they make, and the reasoning for those choices. If they don’t, and they continue to try to be everything to everyone, we are bound to see an ever-greater acceleration of leadership burnout, shorter tenures and fewer people raising their hands to lead. I know I am exhausted just writing about it.

A phrase that always resonated with me is “there are no hecklers on the stage.” Anyone who finds themselves managing today quickly realizes that leadership is much harder than it looks, which is why leaders need to invite more people into the conversation so all stakeholders can better understand the tradeoffs and the realities.

Ultimately, CEOs must direct their focus toward areas that align with a company's values, serve all its stakeholders, keep the company competitive in its market and contribute positively to the broader society. And while there are no easy answers, starting an honest conversation about just how challenging all this is offers a crucial first step towards progress.

The Leadership Minute, available exclusively to Friday Forward premium subscribers, is designed for individuals looking to enhance their leadership skills and build great teams. Each week, you'll receive practical tips, valuable tools, proven best practices, and relevant insights right in your inbox that you can put into action right away.

This is an interesting article. I have heard the same from the leaders I have had the privilege to work with.

The comment at the end about free market at work is a good one. Just as consumers can instantly choose with whom to do business, or more importantly not to do business with (Bud Light, Disney as examples), employees can and do make the same decisions about the organizational value proposition.

There are so many forces and idea colliding in this space at the same time, there is no clear cut answer. Some believe in the concept of shareholder supremacy, the ultimate stakeholder. Others that the purpose of a business is to advance a mission or a cause.

I do believe that more of the granular functions of some of the topics you broach can be delegated, however, direction comes from the C-suite. And the truth is, not everyone will always be happy.

Given the reality of the demands and polarizing opinions of DEI and ESG, the Product versus Culture demands, to be all things to all people at all times is not only impossible, it's completely unrealistic. The question for me becomes, who is ultimately responsible for the org as a whole, as it's own entity? Does the CEO decide the stance on DEI and ESG and delegate the execution of that vision? Is the CEO subservient to the shareholders, the employees, the board, or society as a whole?

One could rationalize making a trade off in share price (Disney) and subverting shareholders' interests in the name of greater DEI and social issue compliance stances. Boeing, hiring an accountant as CEO, does make me question the focus of the organization. The merger of McDonnell Douglas and Boeing set the stage for an organization focused on managing financially as opposed to a focus on collaborative engineering. Now, efficiency has trumped quality and safety and, if you adhere to Milton, the shareholders are suffering more now than ever before. In this example, product/ops overtook quality/people and we see now the result of that. Even DEI is being backed away from (Blackstone) in some large orgs, and the Supreme Court's ruling on affirmative action in universities is adding fuel to that fire.

No easy answers. The worst thing they can do is say nothing. So who decides the direction? Who is ultimately accountable for the org as an entity? I work with CEO's, COO's, CHRO'S and I must say, I do not envy the stress of those roles. Our discussions always come back down to whether their personal beliefs align with the organization they lead, can they effectively communicate those beliefs and vision, and who inside the org is on their side. If they feel out of alignment, burnout is practically inevitable. In fact, burning out and leaving is actually the best case in that scenario. The worst case being forced out after effectively lashing out in a way that hurts the org and their credibility.

It is certainly a brave new world.

Thanks for the piece Robert. Appreciate you!

Nicely written and agree with so much of what you have addressed. I would add that in the Arsenal example and the “business” decision not to honor Ozil with any actions but then to take a stance on Floyd was probably also driven by the size of the market in China and the hard stance the CCP takes to shut down dissent.